Any time a Polish-themed book is published in the English-speaking world, it piques our interest. If the title is The CIA Book Club: The Secret Mission to Win the Cold War with Forbidden Literature, the book gets our undivided attention.

Authored by Charlie English, a former journalist for The Guardian, and published on July 1, 2025, The CIA Book Club focusses on the largely unknown CIA book smuggling program. By operating the elaborate book (and later also publishing equipment) smuggling program during the Cold War, the CIA helped the Polish opposition undermine the communist system and eventually bring it down.

Full of action-packed stories and previously-secret historic details, The CIA Book Club smoothly moves between three “sets” and many “actors”: the US, where critical decisions about funding the program were made by the US government, including CIA directors and president Reagan; Western Europe, predominantly Paris, from where “the middle men” – mostly Polish emigres – operated; and then Poland, the intended destination for the “contraband”. Initially this consisted of books, then from 1982 to1989 – in addition to books – included printing materials, police radio scanners, audio and VHS tapes, and money. The CIA Book Club reads like a suspenseful spy novel, especially at times when the details of specific missions are revealed, down to the names of the people involved, the routes they took, the dangers, risks and often very close calls.

During the time of communism in Poland books, like all other media (films, TV, radio, newspapers, theatrical performances, etc.), were censored by state authorities. It was a preventive censorship, which meant that before a book (or an article, etc.) was published, it was checked by censors for any “improper” content. Censors were given detailed instructions of what to look for. In addition to “improper content”, and good examples of such content could be the expression of any kind of criticism of the Soviet Union or mentioning the Soviets as the perpetrators of the Katyń massacre, there were also lists with the names of writers, artists and intellectuals, both Polish and foreign, who were banned in Poland. Czesław Miłosz for example, after his defection to the West in 1951, was such a literary “persona non grata”. His poems and essays, however, were published in the West, and for instance Zniewolony umysł (The Captive Mind), was published in 1953 by the Instytut Literacki in Paris. That same year Instytut Literacki printed the Polish translation of George Orwell’s 1984. Polish society in general was very much book-oriented, and lines of people in front of bookstores were quite common as the demand for interesting books was usually higher than the supply.

This is the context in which the CIA book smuggling program operated.

Banned books like The Captive Mind, or 1984 were a rarity in Poland, available only to a few people. Many more people knew about them, but either could not get hold of them, or were simply afraid to break the rules of the totalitarian regime and seek this “forbidden fruit”. However, once abroad in the West, Poles often sought them out. That’s what a researcher from Poland who worked at WSU did in the 1980s, once she settled in Detroit: she asked her American friend to get her a copy of Orwell’s 1984. He was able to get her a Polish translation of the book from the Detroit Public Library.

Many of our local libraries have already acquired copies of The CIA Book Club. The interest in this captivating book could be connected to the present political climate, and the instances of “inconvenient” books being removed from classrooms and school libraries.

A case in point is Iowa. Before the 2023 school year, the schools in Iowa were supposed to remove such books as George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm, and Brave New World, by Aldous Huxley – ironically, the “forbidden” books which the CIA paid to make available to Polish citizens during the time of communism. Some of the Iowa schools complied. This purge, initiated by the passing of the law known as “Senate File 496”, allegedly targets books depicting “sex acts”, but in reality, due to the broad definition of a “sex act”, attempts to curtail the access to and remove from schools 450 books that the current Iowa legislature deems inappropriate for young minds.

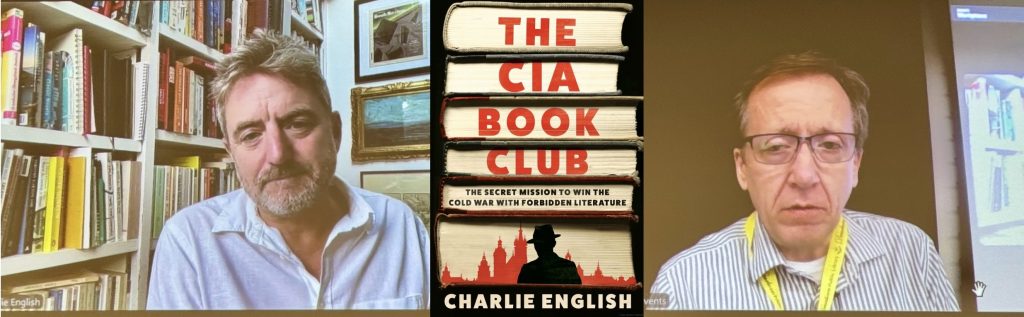

The Dearborn Public Library not only made The CIA Book Club: The Secret Mission to Win the Cold War with Forbidden Literature available to its patrons, but also on October 11 held a zoom meeting with its author. The one-hour long conversation was organized and led by Daniel Lodge, the Library Supervisor. You will find the link to it at the end of this article.

Even now, 36 years after the fact, the broader topic of how much the CIA was involved in bringing down communism in Poland remains a partial mystery. According to Charlie English, most of the documents pertaining to these CIA covert operations are still classified.

English’s work is the second book on the subject. The first one, A Covert Action: Reagan, the CIA, and the Cold War Struggle in Poland by Seth G. Jones was published in 2018. English’sbook partly overlaps with Jones’s book as it focuses on one aspect of the CIA involvement: the “illicit” books program which started in the 1950s and ran through 1989.

If you missed Jones’s book (like this author did) The CIA Book Club, could be a revelation. First, to learn that for many years the CIA paid bookstores and publishing houses for the “illicit” books which the agency recognized as tools of undermining communism, as well as organized channels through which such books were shipped to many countries, with Poland being the biggest recipient of them, could be quite mind boggling. After all, we are talking about the same CIA which is known for stirring up armed conflicts and instigating military coups outside of the US. In this instance, however, somewhat surprisingly, it recognized the transformational power of the books and acted on it.

Also, to find out that – for instance – the famous journal “Kultura”, published in Paris by the luminary Jerzy Giedroyć, and banned in Poland, during its entire run (1947-1990) was indeed covertly funded by the CIA, could come to many as a shock, and not necessarily a pleasant one. “Kultura” during the time of communism was one of the most important and influential periodicals read by the Polish intelligentsia. Smuggled to Poland, and accessible to a relatively small number of people, it was a window into the “free world”. Most of the essays on recent Polish history, or even on the economy published by “Kultura” would not stand a chance to be officially published in Poland because of their perceived anticommunist (subversive) viewpoint.

So, to learn that “Kultura” was able to flourish because it was bankrolled by the CIA, could be like finding out that what one thought of as dirty, revolting, communist propaganda, was actually … the truth.

In the 1980s, especially during martial law, the communist authorities, in their efforts to discredit political dissidents, often mentioned the CIA as the foreign, inimical source of funding of their activities. The intended effect of this message was to discredit the Solidarity movement and its leaders, and make people think of them as “traitors” who did what they did for monetary gain. This propaganda was rather ineffective as most of the people were accustomed to the government lying to them and rejected it. However, as is the case with lies repeated over and over, some of it did stick, and one can argue that the label of “traitors being funded by a foreign spy agency” tarnished Solidarity’s reputation and legitimacy a bit or at least spread some doubts about the purity of their leaders’ motivations.

As Charlie English wrote in his book and stated in his talk, due to the secretive nature of the underground operations, most people involved in them had no knowledge of the broader network they were a part of, let alone about where the money needed to publish, for instance, the Mazovia Weekly, came from. As “conspirators” the least they knew, the better off they and their networks were, so if captured, they could not betray others.

Nevertheless, the CIA involvement in bankrolling Solidarity is still a taboo subject in Poland. As English conveyed in the Q&A part of the meeting, it is also an issue of possibly “stealing the victory”, from Solidarity, if a lot of credit were given to the CIA. The victory, which, as both English and Jones firmly state in their books, was justly earned by the Polish opposition, while the CIA was just aiding them.

In the book, one can read about specific sums of money spent by the CIA on these operations as well as the names of the people and organizations responsible for providing, distributing and receiving the funding. This includes $1000.00 a month for the aforementioned Mazovia Weekly, the most popular of all the publications published underground in the years 1982 -1989. However, the money spent on the book program was only a small percentage of the overall CIA budget and was in constant danger of being cut by the US Congress. At the time most of the money allocated to the CIA was spent by the agency on covert operations in Afghanistan.

During the years 1981-1989 the CIA was one of many supporters of underground Solidarity. The American AFL-CIO, for instance, raised over a million dollars for the cause, and there were other organizations, especially labor unions, in many countries doing the same. It comes as no surprise that the role of the CIA as the major source of money was purposefully and skillfully obscured. For this reason, Western philanthropists and businessmen posed as rich donors and hence effectively removed the CIA from the equation.

The CIA Book Club impresses with the detailed and colorful descriptions of many covert operations. Using personal accounts of people involved in them English weaves a nuanced and entrancing story. Among the stories, the inception of the Mazovia Weekly (Tygodnik Mazowsze). The famous newsletter published its first edition on February 11, 1982, only two months after martial law was imposed. Behind this impressive achievement was Helena Łuczywo. Her story includes her whereabouts on December 13, when she and her husband, due to a mere fluke – instead of being home, where the Milicia expected them to be, they went to the movies, and then wandered the streets of Warsaw for hours – escaped arrest and did not share the fate of over 10,000 other Solidarity activists detained that night. As English states, women activists in general were less targeted by the secret service, therefore after the December 13th, 1981, crackdown on Solidarity, it was the women who almost immediately got to work reconstructing the shattered and headless organization. They quickly recognized the crucial importance of informing society about any acts of opposition to martial law in Poland, as well as about the support for such acts, and condemnation of martial law coming from abroad. The official media would either omit or lie about them and Polish society needed confirmation that despite the harsh restrictions imposed on them by the new military government, they were not beaten into submission.

The publishing of the first issue of the Mazovia Weekly was when “underground Solidarity” was born. In this first issue, there were interviews with three famous opposition leaders: Zbigniew Bujak, Witold Kulerski and Władysław Frasyniuk, who miraculously avoided arrests on December 13 and were in hiding. Two following pages were filled with detailed information about the strikes in the Silesian mines and steelworks which started only a few hours after martial law was imposed. The striking workers demanded the release of the Solidarity leaders detained that night and the end of martial law. The strikes were brutally suppressed by the riot police and military. In the “Wujek” mine on December 16 the riot police opened machine gun fire on the workers who used their tools as weapons. Nine of the miners were killed.

Helena and many others, while constantly changing their lodgings, watching over their shoulders and risking intimidation and prosecution, were able to continue their work. With the help of a huge network of collaborators and enthusiasts – and of course, the funding – they made the underground publishing thrive and kept people’s spirits up.

However, the main Solidarity-era hero English writes about is Mirosław Chojecki. Chojecki, who died recently, on October 10th at the age of 76 was an oppositionist and one of the founders of the “Independent Publishing House” NOW-a, which in the years 1977-1989 published approximately 300 “illicit” titles. English writes about Chojecki’s life as a political dissident and a publisher of illegal literature (known in Poland as “samizdat” or “bibuła”), who endured constant harassment by the Polish secret service, over 40 arrests, and imprisonment. While in prison in the spring of 1980 Chojecki, who was not even informed of what he was accused of, undertook a hunger strike to get a court hearing.

Martial law stranded Chojecki in Sweden and this cemented his future. In the following years, nicknamed “the smuggling minister” he was the key figure of the Polish political opposition abroad, an advisor to the US government and a major collaborator in the smuggling of aid to Poland during martial law.

English describes many very creative and surprising ways in which first the books, and later printing paraphernalia including typesetters and printers were smuggled to Poland by land, and sea, concealed in luggage, train bathrooms, truck cargoes and even Tampax boxes, to mention just a few ways.

I asked the author how the CIA paid for the books smuggled to Poland. English gave the example of the Polish Bookstore in Paris. A visitor from Poland would come there and receive 3-4 “illicit” books for free, with the understanding that after having read them, the books would go to somebody else in Poland, who in turn would pass them to yet another person, and so on. Once a week the bookstore would bill the International Literary Center (ILC), the CIA department in charge of the illicit book operation.

There is a local connection mentioned in both books about the CIA and it is Ms. Cecilia Larkin. Our readers might personally know Ms. Larkin, a younger sister of Jackie Kolowski and the current president of ACPC. Born in Poland, she came to the US as a teenager, grew up in Detroit, and worked in the Polish Variety Radio Program before moving to Washington DC, where she started working for the CIA. In the 1980s Ms. Larkin was stationed in Paris where she was a part of the operation “QRHELPFUL”. In the codename “QRHELPFUL”, the first two letters “QR” referred to Poland, the “HELPFUL” was the name given to the operation of helping the Solidarity movement after martial law was imposed.

Even for readers familiar with the history of Poland before the fall of communism in 1989, The CIA Book Club: The Secret Mission to Win the Cold War with Forbidden Literature by Charlie English, is a fascinating and eye-opening read. The wealth and the nature of information it delivers, and the strength of the individual stories it presents make it into a real page turner.

It is also an empowering story about the failure of attempts to silence the exchange of ideas and free thinking, and the risks people are ready to take to fight these attempts.

I would like to thank Daniel Lodge for bring the book The CIA Book Club: The Secret Mission to Win the Cold War with Forbidden Literature by Charlie English to my attention, and for organizing the talk with the author.

The video recording of the very interesting conversation with Charlie English is available at: