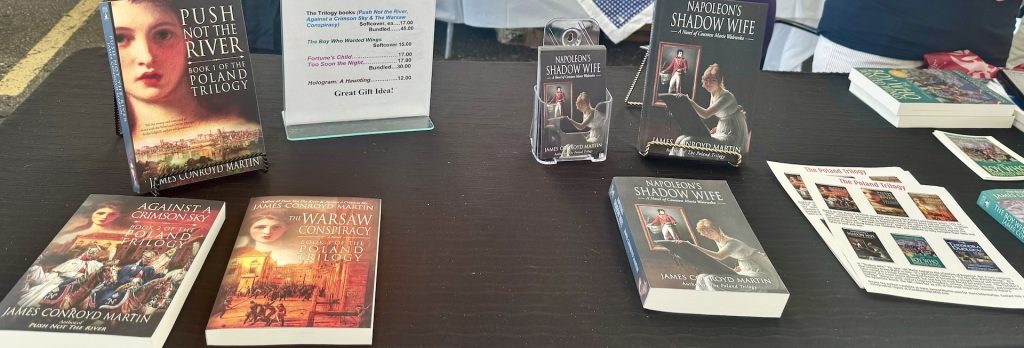

Recently the Polish Weekly had the pleasure of talking with James Conroyd Martin, a writer of historical fiction who is no stranger to many of our readers. He is the author of the very popular “Polish trilogy”, of which the first volume, Push Not the River was published in 2003, and was followed by Against a Crimson Sky in 2006, and The Warsaw Conspiracy in 2012.

The three romance novels have plots set against the turbulent Polish history of the years 1791 – 1831 and were translated into Polish.

In addition, in 2014 Martin published Hologram: A Haunting: (A Paranormal Account of Dreams and Memories Gone Astray). Two years later, in 2016, he returned to Polish history with The Boy Who Wanted Wings which is the love story of a Tatar boy, brought up by a Polish family, and yearning to become a hussar, and a Polish girl. The novel depicts the historical events that led to the 1683 defense of Vienna by the forces commanded by John III Sobieski.

The history of Poland, however, is not the exclusive professional interest of the author, who also wrote two novels that explore sixth-century Constantinople and are centered around the empress Theodora and the palace eunuch and secretary, Stephen. “The Theodora Duology” consists of Fortune’s Child (2019) and Too Soon the Night (2021).

On the Goodreads site, while answering the question about possibly being Polish, James Conroyd Martin wrote: “Ancestry.com says I have a bit of central European blood that inches over into Poland. Quite a bit of Irish, English, and Nordic make up most of the rest.”

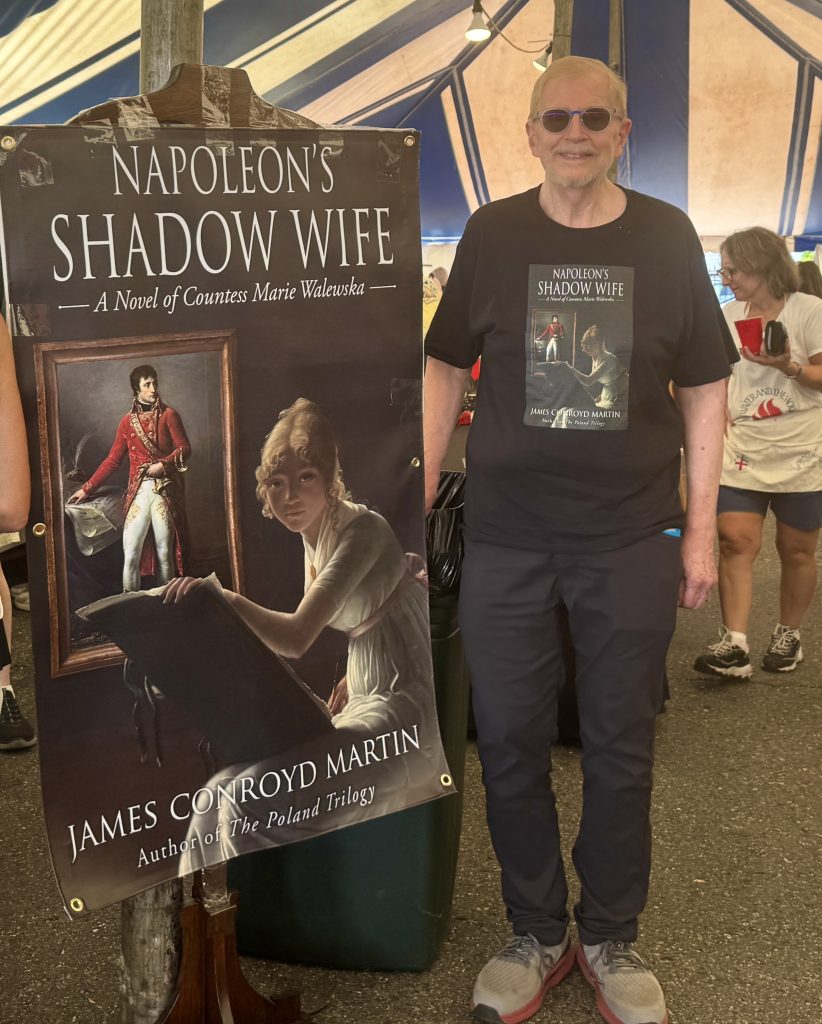

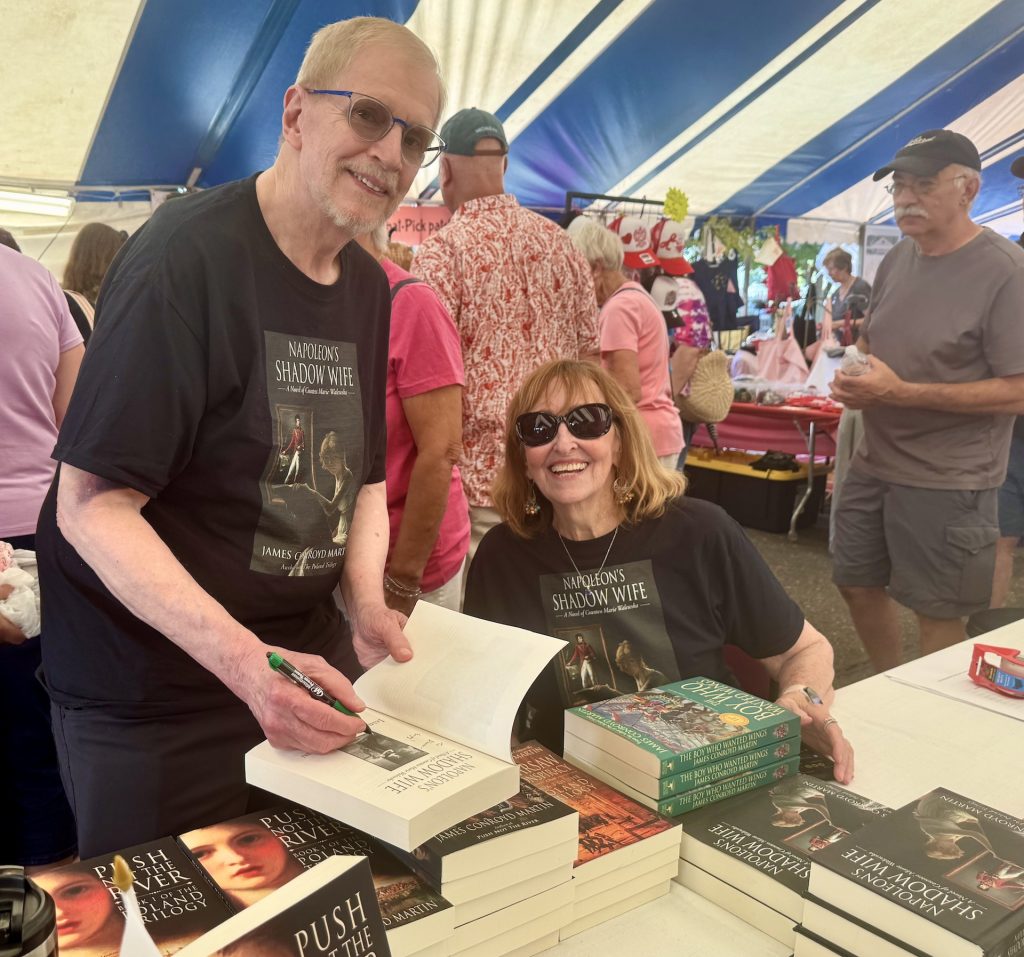

We met with the author at the “Pierogi Festival“ at the Sweetest Heart of Mary Church. Mr. Martin came to the festival to promote his newest book, Napoleon’s Shadow Wife. A Novel of Countess Marie Walewska which was published in April of this year.

Alina Klin: Dzień dobry and dziękuję that you found time to meet with the Polish Weekly. Is it your very first time at this festival?

Jim Conroyd Martin: Yes, it is.

AK: How do you like it?

JCM: It is fabulous; I really like it. This is the second day, and I think it’s going to be really crowded. It is very hot, but we are dealing with it.

AK: How often do you go to similar events to promote your books? I go to Polish festivals quite often and it is a rare thing to see an accomplished, successful author like you to promote a book there.

JCM: Earlier this year I went to the Milwaukee Polish Festival, where I saw Oleńka Lisiecki (“Recultured Designs”), who encouraged me to come here. I met Oleńka in Portland, where I live, and we also have a Polish festival in September.

There are not too many historical fiction books set in Poland, so I have that little area, a niche, to myself.

AK: To some people, who feel that typical Polish festivals promote only certain aspects of Polish culture and not the aspects they would like to see being promoted, you are really a breath of fresh air. I am so glad that there is some traffic to your table, that people are coming up to you. Did you have any interesting conversations so far?

JCM: I did. I first published, self-published, a blue book, with kind of home-made cover, in 2001. My idea was that I would get a big publisher for it, and I did, St. Martin’s Press took it. A woman came here yesterday with the blue book – I was blown away. She found out that I was going to be here, so she brought the book that she bought over 20 years ago.

AK: It was Push Not the River, right? My copy was published in 2003 by St. Martin’s Press.

JCM: Also yesterday, there was this mother and her two grown daughters standing at the picture of the Napoleon’s Shadow Wife and just remarking about it very excitedly, and then they realized I am the author, and she told me how it was her favorite book ever, and that I was her Margaret Mitchell. You know, the author of Gone with the Wind.

AK: That’s wonderful!

JCM: Yes, it was another key moment.

AK: Congratulations on publishing eight novels so far, five of them with Polish history in the background. Poles are very proud of their history, which you know very well, and this alone makes you a Polish hero!

I would like to thank you for popularizing for non-Poles a fascinating and not so widely known Polish history.

JCM: Thank you.

AK: Who are your target readers? Most authors nowadays, when they write, think about a target readership. Be it young adults, be it women…

JCM: Well, broadly, anybody who likes historical fiction, with Polish as my base, as my sub-target. I had people coming to the table and saying, I love historical fiction, it is like you are living in the times. My books are sold at the Polish Museum of America in Chicago.

AK: The protagonist of your latest book, entitled Napoleon’s Shadow Wife is Maria Walewska. Many books were written, and films were made about her affair with Napoleon. Yet you decided to write another one. Why?

JCM: I had heard people talk of Countess Marie Walewska, and I had seen the 1937 film Conquest with Greta Garbo as Marie and Charles Boyer as Napoleon. In researching the second book of my Poland trilogy, Against a Crimson Sky, which covered the Napoleonic years, I could not help but learn a great deal about her. It came as no surprise that Hollywood had invented a good deal of their screenplay.

AK: Were there any historical errors in the film?

JCM: I don’t recall the specifics, but it was a kind of formula Hollywood puts together.

Marie Walewska (born Maria Łączyńska) was an incredible woman. Only in focusing on the woman as the main player in my novel that I came to feel I understood her. In fact, even after I had written the first draft, I was still unsure about having captured her essence. But as I went over the research again and followed through on one rewrite and then another, did I feel as if I came to really know her.

Marie’s story is one of great patriotism. And it is one of an unconditional love that nearly defies understanding. She never intended to attract Napoleon, and yet she did. She had no wish to accept him as her lover, and yet she did. I think she surprised herself when –despite myriad complications – she fell hopelessly in love.

Did Napoleon love Marie? There is a mountain of evidence that he did not. But I think that he did, but not in the unconditional way she loved him.

AK: Poles know the Maria Walewska story, and the gist of it goes as follows: At the time of Napoleon’s Russian campaign, in 1807, a young and beautiful Polish woman, married to a much older man, with whom she already has a child, somehow gets the attention of Napoleon Bonaparte, who – as many Poles believed at the time – could bring Poland back. A group of them want to use Marie as a means to influence Napoleon favorably toward the Polish cause, and “pimp” her out, if you will, to him. She – reluctantly – accepts her role of Napoleon’s mistress, as her patriotic duty.

How could this kind of story be inspirational or even acceptable to today’s women, particularly to young women? Or perhaps it is not the story you are telling in your book?

JCM: Well, it is difficult. She was a mystery; she was a kind of mystery to herself at first. She was a Catholic, spiritual, and she had no intention of linking up with Napoleon romantically…

AK: You made it obvious in your book. She was torn, and – in your book – at the beginning she was flatly refusing such a possibility.

JCM: Even Prince Poniatowski was pushing that she “make nice” with Napoleon, and she did. There are different reports as to how their first meeting went.

AK: Going back to my question, I know it is not an easy one, about a possible reception of your book among the women of today, who could be very critical, for whom “agency” is very important, who are against women being objectified, and could be offended with such representation – how did you address or try to avoid these possible problems?

JCM: I did not try to. I just tried to tell the story. I know that a lot of historical fiction writers today – and a lot of it is written by women – write as if women had more power than they really did. Which is not true in most cases.

AK: So, you were writing “an honest book”, meaning that you depicted the character in the way you understood it. Without any “angle” or without thinking about possible criticism.

JCM: Yes. She had a mind of her own, but she was still a part of her time.

AK: Your Marie is bright, funny, mischievous (at the beginning at least), very intelligent and very well-informed about the politics and the political situation of the day, even – I would say – surprisingly well informed. How do you imagine she got her information? You don’t write, for instance, that she read this, or that… I must say that later in the book I was relieved when Napoleon made his library available to her, at the time when while waiting for his visits, she occupied herself with embroidering.

What was the source of Marie’s very impressive political knowledge?

JCM: She did spend three years in convent school, it was like a finishing school; she learned languages, French. A big thing in her past was the death of her father, she was eight at the time, and they were very close. So, she wanted her country back, for him. Kościuszko was her hero, until Napolean came along …

AK: She truly had to be exceptional. She really lives and breathes the cause of Poland’s independence; the reader feels that this is of the utmost importance to her. I understand that this way of portraying the heroine of the story creates “the motivation” for her to go along later with the idea of yielding to Napoleon’s desires, if you will. She is clearly torn between what she sees and is presented to her as her patriotic duty, and her sincere loyalty to her husband and the institution of marriage.

JCM: The husband treated her as a possession.

AK: Perhaps it is also a statement about the times.

JCM: Yes, and Napolean was like “the hero” of the times, and her husband got caught up in that too. He felt proud that Napoleon was after his wife.

AK: And that is corroborated by historical sources.

JCM: Yes. It was his third wife, it was not like a love match, so…

AK: And it was not either that he needed an heir, because he had plenty… So why did Walewski marry her? Was it because she was available to him?

JCM: Right, and she was VERY beautiful.

AK: I suspect that it serves as a way of making Marie more of a contemporary protagonist, one with agency, not just a “sex object”. I thought that by making your heroine so politicly aware, so patriotic – it all gives her some agency, in this time, when, as you said, women did not have much.

JCM: It is at the very end, at Elba, when she shows the most of her agency.

AK: Your stories tend to focus on female protagonists. Is this hard to write from a female perspective?

JCM: It was at first, but the women in my critique groups, back in California and then in the Chicago area kept me in line. I owe them.

AK: I read a bit about the duology you published about Theodore. One can think that you like “fallen women” as your protagonists. Theodore is a former prostitute, before she becomes the empress, Marie is a mistress.

What draws you to these women?

JCM: Way at the beginning, when I was taking an art course, and we were studying Byzantine mosaics, this was in Los Angeles, the professor said, “This is Theodora, and Justinian is her husband. If I were a writer, this is the woman I would be writing about.” So, I stored that in my head …

AK: I have a close friend in Poland, who is also a writer, and she refers to herself as a storyteller, who just likes weaving stories. And if you like telling stories, you need a topic, right?

JCM: Right, and that’s what I am telling people, I just like to tell a good story, I am not trying to win a Pulitzer Prize.

AK: But who knows? That would be nice!

JCM: (Laughs)

AK: Where did your interest in Polish stories begin? I read that years ago, you left Chicago and settled in Hollywood, California, intent on being a screenwriter. That’s fascinating – did anything come out of it?

JCM: I wrote a couple of screenplays, but I never pushed them, cause then I met John Stelnicki, whose ancestors’ diary my first book, Push Not the River, is based on.

AK: I understand that this diary was never published.

JCM. It was not. We both just wanted to get it out there, not necessarily as fiction. He asked me to read and possibly do something with the diary of his ancestor, Anna Stelnicka, a Polish countess who lived through the dissolution of Poland as a nation (1791- 1831 and beyond). I read it to be polite, coming to realize how much of a Gone with the Wind it was, with two cousins vying for the same man and set against a country and way of life that was passing into history.

And I realized that characters came onto the scene and disappeared, history was not there. If you were writing about today, and politics of today, you would assume that everybody knows the context. And she did. But now people would not know – for instance – about the May 3rd Constitution, so I needed to put the history in, and I needed to make some additions. If somebody was not the main character, I needed to get rid of them somehow later on … So, it became fiction, historical fiction.

AK: So, before this encounter with John Stelnicki you were not interested in Poland or Polish history.

JCM: No. And it changed my life.

AK: Very interesting.

JCM: I thought my second book would be the Theodora book. I was getting ready to present that to my agent to take to St. Martin’s. And they said, well, we’d rather have a sequel. So, Theodora got put on the back shelf for a long time. But eventually it got done.

St. Martin’s Press wanted a sequel and that led to the “Polish trilogy”.

AK: Have you travelled to the places where the events in your novel happen? Have you traveled to Poland, perhaps to do some research or to promote your books?

JCM: Yes, before I published my first book, Push Not the River, I went to Poland. After I went to my hotel in Warsaw, which was near the river, the first thing which I did, I crossed the Vistula and I walked towards Praga, until I got to the bridge… It is a different bridge, but the same place. At the end of the book the Russians are coming down and people are trying to escape from Praga to behind the walls of Warsaw. That’s where I went. The hairs on my arms just stood up because she (Anna Stelnicka) and her cousin faced their death there… almost.

AK: Your books were published in Poland in Polish, with success.

JCM: Yes, St. Martin’s got a Polish publisher for the first two, the first one just after Pope John Paul died, so my book was right behind two or three books about him. He was at the top of the charts, but mine was right there.

AK. I read that – as it was quite popular to do so in her time – Maria Walewska also kept a journal. Is this journal available to the public?

JCM: It is in the family. There is a controversy about it, whether it is true or not. Whatever she wrote after her third marriage, some people think that she tried to gloss over her past for the benefit of her children and her legacy in Poland.

AK: How did you conduct your research for your last book? Were there any surprises you discovered along the way?

JCM: I already had a wealth of books on Napoleon and several on Marie because the second book in my trilogy covers the same years. I continued to do digging, however, through histories and online. Napoleon had a number of odd habits that were surprising. Also, as secure and aggressive he could be on the battlefield and in the presence of kings and popes, he showed insecurity in the presence of his valet and with Marie. Marie’s life decisions were always surprising.

AK: The genre you write is “historical fiction”. How much freedom to be creative does the author have while writing about historical figures?

JCM: I would create scenes, I would know that two people are having an argument, or a disagreement about things. I felt like I could create the scene, and create the dialog, and along with that might come the clothes if necessarily, like when she was worried about people knowing she was pregnant, so she was wearing Regency clothes.

AK: It is a very flattering cut for women today too!

JCM: I did not want to change events, but I created scenes.

AK: Are there any, let’s call them taboos, which you decided to stay away from while “filling in the blanks” in the stories based on historical facts? Perhaps the love-making scenes? I noticed that there was almost none. Not that I think that there should necessarily be any.

JCM: I kind of leave it to the reader. I don’t feel I will be good at it (Laughs).

AK. In your book Maria gives birth to her first-born a little prematurely, while in reality – as I read – the baby Antoni was born only six months after her marriage to Atanasy Walewski. Hence the speculations that Atanasy was not only saving the Łączyński’s estate, but also Maria’s reputation. It would have been someone’s else baby. What is your opinion on this matter?

JCM: I did not want to get into that. I thought I could be perhaps sued by family descendants, and I did not know anything for sure, so I went with what I did know.

AK: About the foods your protagonists are having: a few times I had doubts if what people ate – such as bigos, or gołąbki being served as the main and only dish at a gentry table – was appropriate. How did you arrive at these choices, did you research them?

JCM: I got a lot of books; I learned stuff when I was doing the other Polish-set books. Sophie Hodorowicz Knab – we are in touch, when I have a question, I ask her.

AK: What would you like readers to remember about your story?

JCM: I would like readers to remember Marie Walewska as having led a profoundly paradoxical life. I’ve tried to present the facts with balance, allowing readers to form their own impressions of this singular and multifaceted woman.

AK: What’s a fun fact that most readers may not know about you?

JCM: While living in Hollywood, I attended a one-woman show by Bette Davis. A comment I made as I sat close to the stage prompted her to lean over and invite me backstage after the event. There, I took the opportunity to tell her about the unpublished Push Not the River, and she suggested I send her the manuscript. I did so and received a lovely complimentary note from her.

AK: A great anecdote! Thank you for sharing! If it is not a secret, what are you planning to write next?

JCM: I don’t know if I am going to, I have not planned anything. There is one thing I am toying with … When I wrote about the hussars, I found out that that book did not do as good, because historical fiction readers are women, and it did not do as good as the books I chose to write about women. So, I purchased a few books about Helena Modrzejewska… But I am not sure if I am even going to do it.

AK: I think that you still have a few books in you!

JCM: (Laughs) Thank you! I better be going back to my table.

AK: Thank you very much for talking to the Polish Weekly. I really appreciate your time and your books, and I am looking forward to your next one!

JCM: Thank you!